Discoveries from the Dark Skies of Chile

The Atacama Desert in Chile is one of the best locations on Earth to explore the universe

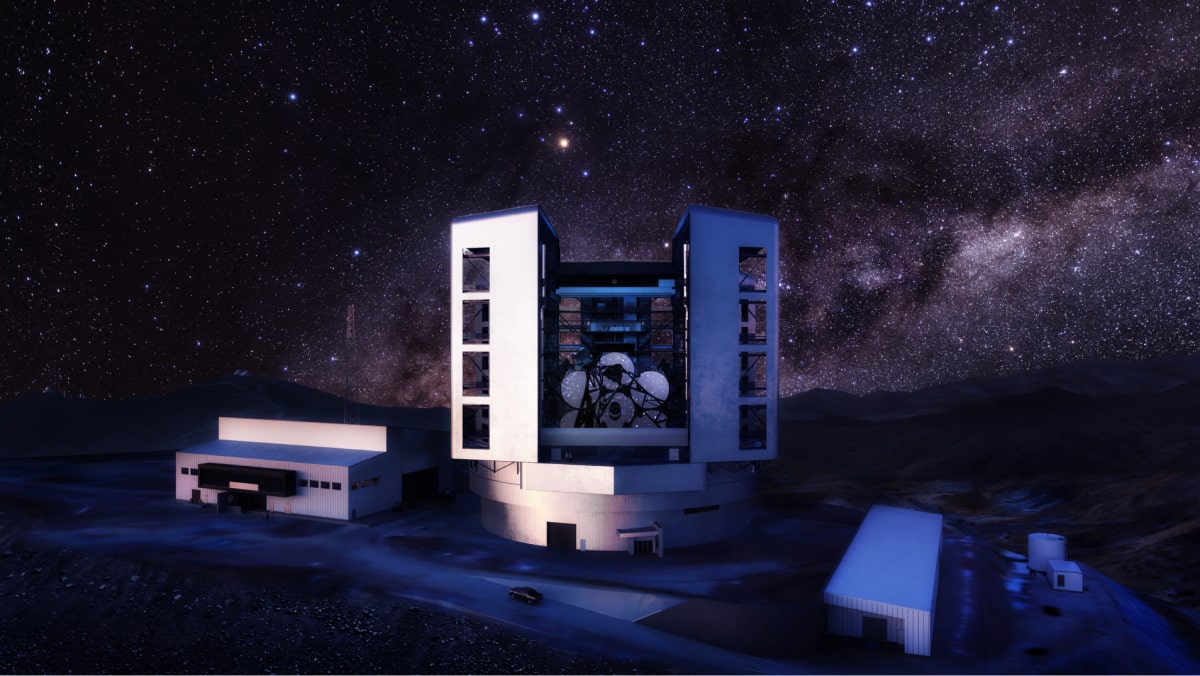

The Giant Magellan Telescope is under construction on Las Campanas Peak at the southern edge of Chile’s Atacama Desert, the driest non-polar desert in the world. The site is located within Las Campanas Observatory (LCO) near the twin Magellan Telescopes, approximately 160 kilometers northeast of the coastal city of La Serena. From here, astronomers will peer into the galactic center of the Milky Way and millions of lightyears beyond.

The location’s high altitude, clear skies, dark nights, and steady atmosphere all contribute to great potential scientific discoveries. Of the many experts involved in the construction of the Giant Magellan Telescope, Former Vice President Miguel Roth, Chief Scientist Rebecca Bernstein, and Vice President and Legal Representative in Chile Oscar Contreras-Villarroel, share their experience at LCO, the importance of science specific to the Southern Hemisphere, and the collective effort to preserve Chile’s dark skies.

How have you seen astronomy grow during your time at Las Campanas Observatory and what makes it such a special place?

Former Giant Magellan Telescope Vice President and Former Las Campanas Observatory Director Miguel Roth:

When I arrived at Las Campanas Observatory in 1978, it was relatively small, with two other resident astronomers and relying mostly on the technical support of Carnegie Science’s staff in Pasadena, CA. LCO had already made significant contributions in diverse areas, like the imaging of the first circumstellar disk, Beta Pictoris, the discovery of the Supernova 1987A, and other important discoveries. Since then, it has developed enormously. The amazing development of knowledge in astrophysics over recent decades goes without saying.

On a local scale, the impact of LCO and other international observatories in the development of Chilean astronomy is huge. In the late 1980s, the number of professional astronomers in Chile was of the order of 20. These days, there are over 220 astronomers with a Ph.D. in various departments, groups, and universities in the country.

The location’s scientific value is supported by seven decades of active telescope use including the Swope (1971), du Pont (1967), and Twin Magellan telescopes (2001). During my nearly 25 years serving as the Director of LCO and being part of the construction and operations of the Twin Magellan telescopes, I’ve seen major astronomical breakthroughs, including the beginning of the first synoptic galaxies radial velocity surveys, the exquisite improvement of radial velocity measurements for the detection of exoplanets, the discovery of the most distant black hole, and the first spectrum of a neutron star-neutron star merger. Today, LCO continues to play an important role in modern astronomy through follow-up observations of astrophysical phenomena and objects with a variety of instruments.

The Atacama Desert is a special place and taking care of its dark skies is a priority. The Southern sky is home to many of the world’s most advanced ground-based telescopes and with the addition of the Giant Magellan Telescope, it will continue to be the world’s premier astronomy research center.

What are astronomers interested in viewing from the Southern Hemisphere and what types of scientific discoveries do you anticipate from these observations?

Giant Magellan Telescope Chief Scientist and Carnegie Science Staff Astronomer Rebecca Bernstein:

The Giant Magellan Telescope’s location in the Southern Hemisphere is ideal for observations of a lot of unique targets, including the center of the Milky Way, the nearest star that hosts potentially habitable planets (Proxima Centauri), and the Magellanic Clouds, to name a few.

There are also a wide range of observatories that will be or already are operating in Chile and Antarctica. They’re there for the same reason the Giant Magellan Telescope will be — because of both the astronomical and geographical advantages of their sites. The science from all of these observatories is infinitely greater when we can study the same objects and phenomena with complementary capabilities. To give just one example, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is currently a few years from operation. When it’s complete, it will begin a survey to find “transient” targets — which are basically exploding stars that evolve dramatically in timescales of minutes to days. We’ll need to take spectra of those to gain the scientific benefit of those discoveries, and that will require a telescope the size of the Giant Magellan. With those spectra, we’ll learn about the physics of those explosions, the galaxies they reside in, and identify their locations in space to track the expansion of the universe. And that’s just the beginning.

What really makes the future of the Giant Magellan Telescope so exciting is discovering the unknown. These unexpected discoveries will provide humanity with new perspectives of our place in the universe and provide new questions about things we never knew existed.

As city centers and large suburban areas grow, how is Chile staying at the forefront of dark skies preservation?

Giant Magellan Telescope Vice President and Legal Representative in Chile Oscar Contreras-Villarroel:

Dark regions far away from sources of light pollution are best for viewing the faintest objects in the universe. From LCO’s remote location, the Giant Magellan Telescope sits away from light pollution and in the thin atmosphere of Las Campanas Peak. This is one of the unique qualities of the Atacama Desert.

The Giant Magellan Telescope is committed to preserving the dark skies of Chile and our team is working to mitigate light pollution in the Atacama Desert and in the country. We are doing so by working collaboratively with all of the international observatories in Chile, along with the Oficina de Protección de los Cielos del Norte de Chile (OPCC), a technical office providing advice to any city, location, or organization that requires it in Chile, and the Fundación Cielos de Chile (FCC), a non-profit organization promoting the importance of dark skies protection and mitigating light pollution by implementing outreach programs and working with the local government to improve measurements and protect the skies.

We celebrate the efforts of the government in implementing the new light norm (the regulatory body for public and other open spaces illumination, and astronomy-friendly fixtures), that in 2023 declared 29 towns in the north of Chile as “astronomy areas” to enhance dark sky protection, thus leading a national movement to protect the night sky for every citizen and for astronomy research. This will make Chile the capital of astronomy, concentrating around 70% of the worlds ground-based astronomy infrastructure by 2030.

Read more about Las Campanas Peak here